Art & Antiques, May 1989 Back to Bibliography

Autun. Spring, 1986. Brooding skies above a provincial city; rain coming down hard, then a patch of blue. It took three trains to travel the fifty-odd miles between Dijon, the old capital of the dukes of Burgundy, and Autun, a center of religious activity in the Middle Ages.

They were little trains, with French schoolchildren on overnight outings supervised by exhausted-looking teachers. Going on these local rail lines, looking for a place to grab a bite around the

perimeter of Autun's vast, asphalt-paved square, we experienced the traveler's mixed sensations of tedium and exhilaration, the emotions coming fast, one on top of the other.

The "we" is Deborah Rosenthal and I, artist and writer, married for sixteen years. When we've been lucky enough to take in the sights of France, it's been in quick, deep gulps. However much we'd like to linger—to be as we imagine the tourists of earlier ages to have been—

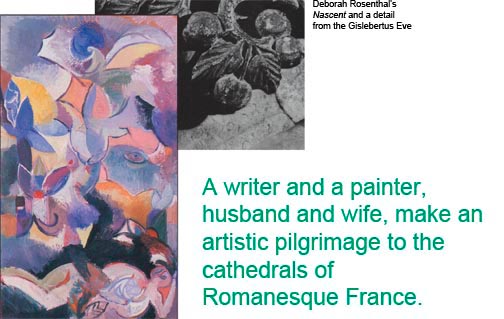

And here we are in Autun, the city of the twelfth-century sculptor Gislebertus. We're standing outside the cathedral, before the hieratic symmetries of the tympanum, and then inside, amid the capitals, a forest of google-eyed monsters and men and women with the proportions of children. I remember it all in flashes: the low light in the cathedral picking out the crisp stone carving; the soft emerald vistas seen from the windows of the tower; the little antique stores folded away in the houses around the cathedral. And I come back to it now, a couple of years later, when the snakelike Eve (also by Gislebertus) that's in the museum across the street from the cathedral appears as a mirror-image in a painting of Deborah's entitled Nascent. The surface of the painting is neither dark nor light, but veiled, shimmering. And out of this misty realm blossoms forth a bouquet of In the painting modern art twists back to the Romanesque. It's logical that a Jew should feel attracted to early Christian art—to an art that, like Judaism itself, is wary of naturalistic representation. Whatever this Romanesque world is, it isn't something made in our image.

ornamental forms, as well as a staring eye, a tiny figure, and a ghostly blue face. All of this reminds me of the rainy spring day in 1986 when

Gislebertus's sharply carved capitals worked their storybook magic.

Eve—

Eve—sleepy, sensuous—is just right as the catalyst for a recollection of Burgundy, because Burgundy, this miraculously green place, is itself a kind of Garden of Eden. To the Romanesque sculptors of Burgundy—who were immersed in the creation of a stylized universe, a universe suited to the glory of God—the beauty of nature had to be left at the entrance to the cathedral. The cathedral itself turned inward, and embraced the forms of nature only insofar as they could be transformed by a pious, antinaturalistic idea of style. And today, at Autun, we turn back and forth between the tilled fields, as precisely defined against woods and sky as landscapes in illuminated manuscripts, and the stone cathedral, in whose decorations we rediscover idealized nature, nature as symbol.

Nature past versus nature present. Nature in the early art of Europe versus the nature we all see as we walk down to take a swim in a country lake. In certain of Deborah's paintings I have watched as these two ideas are united in ways both daring and lovely. All this interests me as an interested party; it is odd and risky but also pleasurable for once to be writing of paintings familiarly, having occasionally looked at them as they evolved, and, more important, been privy to the artist's thinking as it evolved, step by step.

Take The Righteous Person Flourishes as the Palm Tree. Here the whole of the tree, from roots up to fronds, is as tightly lashed to the rectangle of the canvas as the forms in a Jesse tree are lashed to the stained glass of the Gothic window. And from the spreading branches of Deborah's tree grows a human head, like a fruit nearly ready to be plucked. (The fruit-as-head is an idea invented by Odilon Redon—a painter of stained-glass visions and a favorite of Deborah's.) The Righteous Person, with its bright, almost fruity passages of orange and green, red and blue, comes out of a time of great happiness and intensity—a time when we were away from New York, living in the country, and I was writing, and Deborah was painting, and our son was swimming and exploring. Of course, I know as I write this that Deborah will point out that a smaller version was completed in New York, the winter before. . .Yes, but the color, the sense of resolution in the final version seem to me to be connected to that summer. The smaller version is pale, fragile; this one is bold, resolute. I read the boldness as happiness. And in the painting the happiness at being upstate for the summer is mingled with the happiness of Autun.

When I asked Deborah where she'd found the inspiration for the head, she

took a postcard of a capital at Vézelay, another Burgundian pilgrimage town, off the wall of her studio, and there was St. Martin standing beneath a palm tree. On the capital the relation of man to nature is presented telegraphically—

After the carved tympanum of Autun and the cool forest of columns inside, we had a snack near the cathedral in an old-fashioned shop with a counter in front and a few tables to one side. Many people go to Burgundy for the food, but we keep kosher—Deborah more strictly than I—and so food has never been a particularly important thing for us when we

travel. Sometimes it's been a problem; but being kosher can also be clarifying, reassuring. And, really, there's a connection

between what makes eating in a place like Burgundy difficult for us, and what drew Deborah to Burgundy in the first place.

When Deborah and I met at Columbia University in 1970—a meeting, during the strike against Nixon's invasion of Cambodia, that makes one of those picturesque stories that we all like to tell about our earlier selves—I was struck more than I knew at the time by the fact that this Barnard junior, who roamed around campus in army fatigues, was also an observant Jew. At eighteen, I was

catapulted into a confrontation with my own Jewishness, a confrontation that has, over the ensuing nineteen years, resolved into an intimate—but somehow, to me, still inexplicably intimate—relationship with Jewish observance. Keeping the sabbath, for instance, has become something I do without quite understanding why—

In any event, Deborah has found, inside the clear yet enigmatic forms of early Christian art, shapes to fit her own faith. It's logical that a Jew should feel attracted to early Christian art—to an art

that, like Judaism itself, is wary of naturalistic representation. The design of the Romanesque capital or tympanum is, like the design of the Old Testament narrative, big-scaled, rough-hewn. Events arc presented bluntly, without the polish that a realistic view of the world can afford. Whatever this Romanesque world is, it isn't something made in our image. And, like the motivations of the characters in the Old Testament narrative, the motivations of the characters that Gislebertus carved at Autun remain mysterious, at least to the prying inquiries of our modern, psychologically oriented minds.

Romanesque art offers us large, indivisible symbols—Man, Woman, God. And part of what attracts us is the twelfth-century artists' ignorance of what we regard as conventional musculature and anatomy. The indifference to anatomy is a tipoff to the fantastical nature of the Romanesque, to the artist's willful detachment from life as lived experience. Gislebertus did not care about the humdrum facts of male-female relations. Deborah always points out that the pose of the lower body in the Christ on the tympanum at Autun (though anatomically impossible) echoes the position of a woman giving birth. She has used that Christ as a model for female figures, such as her Female Student of Kabbalah. And for Initial Figure, which is neither clearly male nor clearly female (though it has, for me at least, the aura of a self-portrait).

In some of her paintings, Deborah is weaving a personal mythology—a modem artist's mythology—around the figures of this distant past; yet there's a conflict here, because, as Deborah has said, "Sacred art isn't possible any longer. No one person can make sacred art." So the question becomes how a modern artist—who is essentially an irreligious artist—

I'm not at home as I write this; and when I go over to the small upstate library to see if I can find some reproductions of Romanesque sculpture to look at, the single book that has any is Andre Malraux's Voices of Silence. What an audaciously regal book it is, this stately art-historical prose poem written in a language that's mannered, but just mannered enough. The litany of Romanesque place names—Autun, Vézelay, Moissac— has the force of a pilgrim's chant. From Autun Malraux reproduces the Eve that Deborah and so many others admire, and a grave, bearded head, and a group of figures from the tympanum.

My eye has been caught by that gaggle of meek little figures on the tympanum. They're but half-formed, without the elaboration of features and In France, Deborah and I found ourselves walking down two corridors—one led to the secrets of twentieth-century art, the other led to the secrets of early Christian art. Only after our trips were over and her paintings painted did I really understand the significance of that earlier world.muscles that came into European sculpture a hundred

years later. Their personalities seem unformed, too—and Malraux writes about this. He reproduces, on adjoining pages, two closeups of eyes: one, less naturalistic, from a Romanesque sculpture; one, more naturalistic, from a Gothic sculpture. "The Romanesque eye began as a sphere inset between the eyelids, a sign," he says; "the mouth was a sign for two lips; the head was a whole that was merely a supreme sign." This idea of the eye and the head as "signs" is something that I recognize from Deborah's painting, which is why Nascent is Romanesque, not Gothic. Deborah loves the wide-open amazement of the Romanesque faces, their beautiful, gentle awe.

Images of Burgundy overlap. A year later, after spending a night in Vézelay, where the Christ on the tympanum is crazier, more expressionistic than the one in Autun, we walked down the steep hill to the little Church of Notre Dame in St-Pere, a fifteenth-century Gothic jewel-box in stone. Farewell to the Romanesque. It started to rain heavily, and we decided to take an earlier-than-planned train back to Paris.

In France, Deborah and I found ourselves walking down two corridors—

Back to Bibliography