Photo: Willy Nash

Paint, glass, light and steel: different artists on show around New York transform materials into something vital and organic.

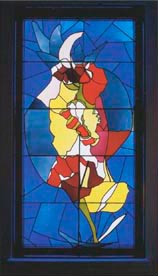

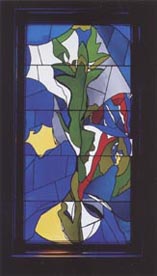

. . . Deborah Rosenthal is a painter who knows just where she stands in relationship to nature. For years, Rosenthal has been combining elements of dream and myth with religious subjects, including the Garden of Eden and the figures of Adam and Eve, in her abstract paintings. Recently, she was commissioned by Minyan M'at at Ansche Chesed Synagogue on New York's Upper West Side, to design two stained-glass windows to flank the ark of the Torah in the synagogue's sanctuary. The windows are identical in size, each is two and a half feet wide by five feet high, and they are approximately 25 feet apart. In a recent television interview, Rosenthal stated:I don't think it is possible to create sacred art at this point. Sacred art is the collective expression of a society. Even among religious people there isn't an audience that readily understands all of the signs and motifs . . . what I'm doing is working out of my own belief, out of my own obsessions, some of which have to do with religious thoughts, religious impulses; but I know I have to speak to you as the viewer, whether you are moved by a religious impulse yourself or not.To do this, to speak more universally, Rosenthal explored nature as a metaphor, wedding architecture and organism through abstract form.

|

|

|

| Deborah Rosenthal, Pomegranate (left) and Tree of Life (right), both 2001, stained-glass windows for Ansche Chesed Synagogue, New York, each 60 x 30 in. Photo: Willy Nash |

||